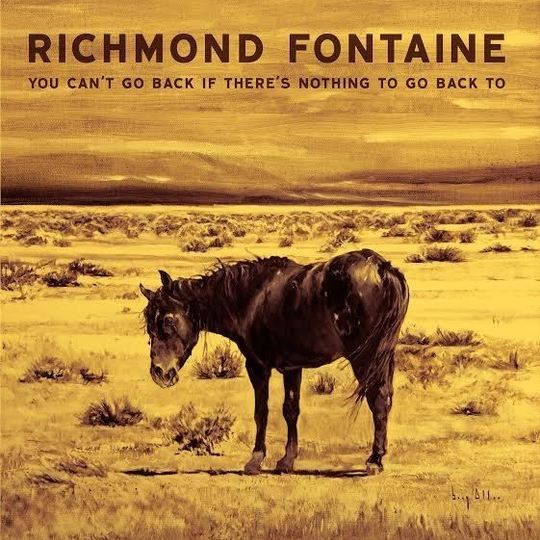

What you need to know is that this is going to be Richmond Fontaine's last album. Knowing so will lend the listening experience an extra indulgence, not unlike the way you feel right after a serious breakup. You know, where you scan your mind for every discernible reason not to have done what you just did. Knowing an experience is over makes you look for all its best features, and forgive its flaws as proof of humanity. Of course, Richmond Fontaine hardly deserves any kind of apologetic treatment, if for no other reason than You Can’t Go Back If There’s Nothing To Go Back To is a lively statement at the (supposed) end of a 22-year-run.

Proceedings begin with a sunrise instrumental, 'Leaving Bev’s Miner Club at Dawn'. Knowing what we know about this being their last album and all, it sets an immediately bittersweet tone. The image is mixed: the night and the party are over, but a promise of renewal awaits. The night wasn’t long enough, sure, but it never is. From there, each song reads like a different image receding in the rearview mirror of a 22-year-old car. 'Wake Up Ray' leads a series of disconnected thoughts—“Ain’t no use, oh it ain’t no use…Maybe some guys just ain’t meant to…”—into bitter (but survived) memories of an unsuccessful marriage: “Got to where she cringed at the way I slept and ate…I can’t stop thinking, how can someone you love so much turn against you so?” The deliciously hook-driven refrain sees the narrator shaking his friend Ray awake, anxious to move on. Like “Leaving Bev’s” the morning promises something, but what it is ain’t exactly clear.

Distant memories of very specific people undergoing very detailed small-town American suffering —Whitey in 'Whitey and Me', Uncle Whittler in 'I Can’t Black Out if I Wake Up and Remember', plus a thousand more — fuel the remainder of the songs. It’s an exhaustive—borderline exhausting—account of an American everyman. A cuckold defends himself: “You’re fucking that guy that you used to…I don’t care if she plays my old Armstrong records for him” ('Two Friends Lost At Sea'); a drifter suffers, ruminates on suffering: “I got so sick behind a car, slept against a bank wall, ate at Annie’s Donuts, made it to work on time…is this what life is?” ('A Night In the City'). The down-to-earth – right down to the ground – details are both funny and harrowing, and they reward close attention with a lot to chew on.

The pitfalls are twofold: the sound, though crisp and appealing, is very familiar. It owes a lot to Springsteen’s melancholic romanticism, and strongly recalls Wilco’s earliest attempts at high-minded folk-rock. And, like Springsteen, each song has a lot of detail to follow, and as you become more and more familiar with the songs’ appealing-if-monochromatic sonic palette, you start to lose track of what took place where and who was involved with what.

In the grand tradition of melancholio-romantic albums, You Can’t Go Back ends with a piano ballad. Between another series of nicknamed, hazy-from-these-years characters – Flanagan, Cassie, Old Leon, and his wife, to name a few – living it up in the paradise of the past, the narrator wonders: “Do you think an easy run will find me?” As an album loser (and, supposedly, a career-closer) that aims at a gut-buster, it delivers. An hour of reminiscence later, one wonders: does it get easier? Probably not—but Willy Vlautin and the rest of Richmond Fontaine should find some comfort knowing that at least they’ve given a good amount of themselves.

-

7Dustin Lowman's Score