Hauschka records make for peculiar cultural artefacts. Granted, in some sense they’re just almanacs of Volker Bertelmann’s fidgeting, mechanical prepared piano compositions. But there’s a historical baggage, too: back when the piano took office from the ageing harpsichord, it was swiftly heralded as the instrument that would furnish generations of musicians with a brand new palette of sound. But slowly, the tinkling of ivories lost began to lose its novelty, and it quickly fell to one Mr. John Cage to reinvigorate the sound of the instrument once more. Cage ‘prepared’ his piano, drastically distorting its sound by inserting surplus materials from his local B&Q (nuts, bolts, scraps of metal and plastic, etc.) between the hammers and strings.

A few particulars aside, it’s this prepared piano that Bertelmann has come to inherit. But Hauschka’s position in this (very condensed) history isn’t quite that straightforward. Bertelmann’s instrument of choice may invoke very specific historical associations, but musically, he’s not interested in Cage’s avant gardisms, nor does he compose with the spectres of Liszt and Schumann breathing down his neck. Instead, new set Abandoned City takes as its point of departure a type music that’s only existed since digital developments have rendered the very problem of finding ‘new’ sonorities somewhat redundant (electronic, dance-oriented music). What we’re left with is a kind of chronological mismatch between ‘now’ and ‘then’; of history folded back in on itself.

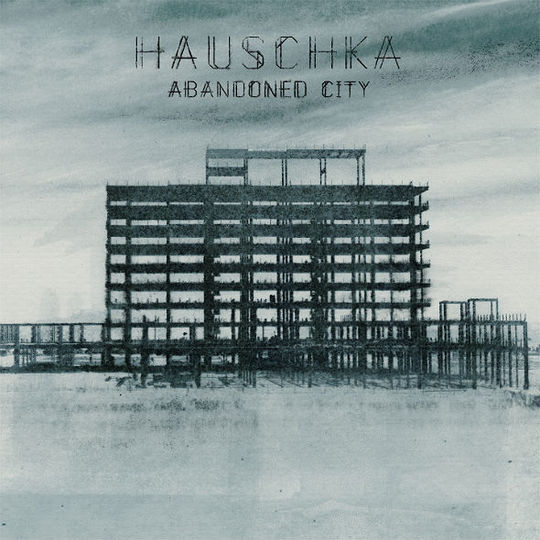

This vaguely archaic quality pervades Abandoned City (the clue, after all, is in the name), and the sense of Bertelmann’s antiquated instrument shaking, rattling—almost falling apart—is more palpable than ever before. Where 2011’s Salon Des Amateurs made a selling point of its precise rhythmicality, Abandoned City deals in rough approximates. Erratic echoes tremble uncomfortably on the peripheries of ‘Elisabeth Bay,’ and hollow percussive knocks line the edges of ‘Agdam’.

What’s impressive is that every one of these vastly different textural components originates from that same, historically freighted source (the piano). Hauschka’s innovative ‘preparations’ can be held partly accountable, but so too can his recording setup. Nine microphones preserve the sound of hammers hitting the strings exactly as they’re heard, with a further three passing through an effects unit – if Bertelmann is unable to render a desired sound through physical adaptations, digital manipulations provide a fruitful workaround. (See Matthew Herbert’s One Pig for similar, albeit more leftfield, approach to cutting a whole tapestry from a single cloth).

It’s this modest system from which Hauschka creates Abandoned City’s nine tracks – each evidently named after a specific vacant city around the world. On paper, that’s an interesting conceit, but there’s the odd geographical misfire here. Take ‘Thames Town’, apparently after a newly built, quickly deserted Chinese city – almost immediately, it evokes a sense of some dancehall-indebted R&B track from the forgotten days of MTV Bass. The same goes for ‘Sanzhi Pod City’ – a track that presumably, again, shoots for the Far East, but after a fairly severe ricochet ends up in Kingston, Jamaica instead. Thankfully, these bewildering cross-cultural tangents are few and far between, and they’re swiftly erased by the likes of ‘Craco’ (inspired by a medieval Italian village) – at its core a study in gentle minimalism, the piano sound stripped of all its ‘preparations’.

Let’s face it, Bertelmann’s carved out something of a niche for himself as a prepared piano composer-performer – on this virtue alone, he can claim some points for originality. By extension, Abandoned City is a fascinating study of exploiting a modest toolkit far beyond its means. But ultimately, while Abandoned City’s atmospheric appropriations of various strands of dance music make for interesting listening, you might wish they appealed to instinct as much as they do the intellect.

Album Stream

Hauschka - Abandoned City by City Slang

-

6Sam Cleeve's Score