Alex McAulay is a writer who churns out young adult fiction for MTV books. In the Nineties he was a musician who went under the alias Charles Douglas. Prolific, yet erratic, Douglas could never quite get a handle on his talent; there was never enough focus to put together a release that truly meant something.

Listening to The Basement Tapes is like picking through dozens of cardboard boxes left by your dearly departed Gran in search of valuable antiques. Likely you’ll just find empty brandy bottles and hundreds of Avon catalogues. Therefore when approaching such a collection you need to be prepared to endure ropey amateur recordings and plenty of unlistenable garbage. But there are lo-fi gems to be found, charming offbeat songs like ‘Monkey Island’, ‘The Golden Age’ and ‘If’ has a tainted brilliance about them.

McAulay emerged from a mental hospital in the Nineties, and similarly to the recordings of Daniel Johnston, the music is battle scarred, child-like, yet quite despairing. The wistful way that he croons suggests a sad balladeer, not happy with his life. There are a number of songs which talk of loneliness, and paint the picture of a talented man recording for days on a battered 8-track in some dingy apartment with only a cat for company.

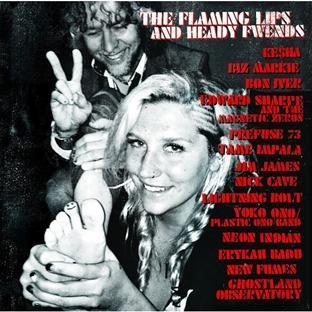

Bad luck and difficult circumstances probably prevented anyone from exploring Charles Douglas, even though he had a few cheerleaders and was a face in the indie scene, hobnobbing with some rad bands. Commercial indie rock was massive in the States during the mid-Nineties – the likes of Beck and Pavement, bubbling under that you had acts such as Guided by Voices, then you had the influence of mentally ill mavericks such as Daniel Johnston and drug addicted home recordings such as John Frusciante’s Niandra Lades and Usually Just a T-Shirt. All of which can be spiritually connected to Charles Douglas’s recordings. For whatever reason, and despite working with the likes of Moe Tucker from the Velvets and one of the finest rock guitarists in the form of Joey Santiago from the Pixies, Charles Douglas never made any significant impact.

Douglas is able to write a tune. ‘In With The New’ is an astounding effort, the bucketful of longing ‘Where The Sky Touches The Ground’ and the sharp ‘Thee Hipster’ reveal a songwriting talent ahead of his time, playing to an appreciative audience somewhere in the future. This is despite the crude use of a drum machine that provides a dated percussion. If I were to pick out more gems from this collection, I’d single out ‘Chapel Hill’, ‘Frequent Flyers’ and ‘Aleka’.

I’d like to touch upon the spectre of mental illness that hangs over the singer songwriter, the prolific obsessed talent that is possessed by the music and the pursuit of writing the perfect imperfect song. There have been equally single minded artists that have had a far greater influence than Charles. I’m thinking of Elliott Smith, Mark Linkous and Vic Chesnutt who were ultimately defeated by their demons. The question remains – what went wrong? Obviously circumstances were different for all three men, but they had the talent, they had the enduring songs, they all meant something to thousands and thousands of strangers all over the world. The same question can also be asked to both the surviving artist, and the retired artist who never was rewarded either critically or financially for their works. Charles Douglas is another artist for whom we can only ask – What went wrong?

This collection is worth picking up, purely because it is nice as a listener to have a rummage around 60-odd songs in the search of something good; the challenge might be to narrow that batch down to ten songs worth keeping, and to forward those songs onto someone you know. They say one man’s trash is another man’s treasure, and there are a few rare gems here. Charles Douglas may not have made an impact during his time, but nowadays music is timeless, and the borders and boundaries don’t exist like they used to, generations ago.

-

7Richard Wink's Score