As the so-heralded 'Summer of Love' descended onto the predominantly white districts of Haight-Ashbury, the worldwide perception of America seemed to be that of a nation embracing peace, love, unity and freedom. A land of opportunity; a land of brotherly love: both physical and spiritual bonding. But as the restrictions loosened and the tabs of acid were dropped, another more unedifying chapter in American history was still being played out with increasing exposure across the wireless and television sets of the day. Though substantial progress had unquestionably been made in the battle for black civil rights in the USA, each push for constitutional rights and the removal of hated, out-dated and draconian laws on racial segregation was still being met with obstruction and foul racism; in many cases from senior figures in the US political system. Against the frustrating grind and a perceived notion that the drive for change was not occurring quickly, drastically and (more importantly) combatively enough and as a diversion from the non-resistance movement practiced by the likes of Martin Luther King Jr.; The Black Panther Party was formed in 1966, quickly assuming a large degree of public support amongst frustrated young Black Americans. And so it was, that on May 2 1967, 11 days before Scott McKenzie released his classic version of ‘San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)’ – soon to become the anthem of the hippie movement – approximately 30 armed black men and women in black berets invaded the courtroom steps of the California State Capitol, Sacramento, to protest against repression and legislation. Though initially a small protest, news of the forceful stand carried across many miles and served to galvanised a generation. From small beginnings, the era of Black Power had begun.

Across seven years, the ideological theorums of Black Power crossed over the race divide, and gradually assimilated itself into the culture and surroundings of the era. Based upon a firm set of moral codes and a championing of pride in black culture, the influence of the movement spread into music: twisting music and lyrics into something more forthright and puffed with pride. Though initially a rebound of the political ideology, the music of the Black Power era eventually became central to the whole culture of the movement, lighting a touch paper that would eventually result in the politicisation and the unheralded explosion of hip-hop and Black cultural influence nearly two decades on.

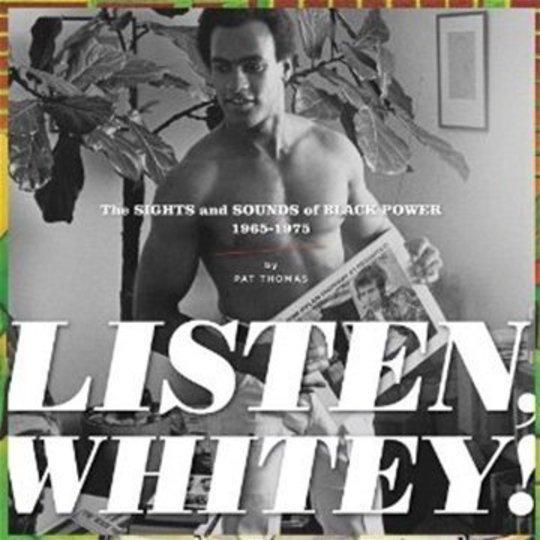

Listen, Whitey, The Sounds of Black Power 1967-1974 is the musical accompaniment to a labour of love and dedication by music producer and scholar Pat Thomas over the course of four years – interviewing leaders of the Black Power movement and collating music and artwork to piece together a 70,000 word tome on the sounds that defined a key movement and moment in Black American culture. Contained within the CD are a series of rare, rich and fascinating tracks inexorably linked with the Black Power movement. From Motown’s short-lived Black Forum offshoot label, to the crossover between White and Black artists shouting for the same goal from differing perspectives and positions, it is a fascinating and captivating listen: equal parts history lesson, musical scholarship and a profound, humbling and richly textured listening experience.

A collection of archive audio, speeches, spoken word poetry, comedy and music, the album admirably draws from disparate corners of the cultural field. It shuns such behemoths as Marvin Gaye’s ‘What’s Goin’ On’ and James Brown’s ‘Say it Loud - I’m Black and I’m Proud’, instead seeking for lesser-known nuggets. Shahid Quintet‘s opener ‘Invitation to Black Power Parts 1 & 2’ sets forth a spoken word agenda to a thumping jazz clatter: a stark call to arms invoking Elijah Muhammad and warning against individual acts of violence in favour of collective action and strength in religion and community. The soaring tones of Elaine Brown - a singer with close ties to the Black Panthers – pour forth on the glorious, stirring cry to hope that is ‘Until We’re Free’, while Marlena Shaw’s live version of ‘Woman of the Ghetto’ (later sampled on Blue Boy’s ‘Remember Me’) forms at a crossroads of jazz and early funk: taut and spiked in delivery yet loose and bubbling musically. The late, great Gil-Scott Heron - one of the true pioneers of politically charged funk and soul music - is represented here by the sparse, elegant and poignant ‘Winter in America’. And then there is the swirling drum, organ and vocal clatter of Gylan Kain’s ‘I Ain’t Black’: twisting racial slurs and retorts into a free-jazz maelstrom of fury and confrontation. It is the track that stands out as the heartbeat of the record, perhaps best encapsulating the contrast of righteous indignation, confusion and self-belief that characterised the drive for rights, identity and acceptance amongst young Black Americans. Throughout all is a sense of dry humour that continues to shine through. Even in the bleakest moments, there remains the ability to laugh at, point and mock the absurdity of the situation. Talk about confidence…

The recordings of speeches are fierce and blunt. Activist Stokely Carmichael’s electrifying ‘Free Huey’ speech ties the persecution of Black people and specifically jailed Black Panthers co-founder Huey P. Newton to the elimination of the American Indians and the conflict in Vietnam; imploring Black union. And then there’s comedian Dick Gregory’s ‘Black Power’, which starts out as a comedic skit but ends up making a series of profound reflections of the uses of the words 'black' and 'white' in popular culture. As an adjunct and a measure of the importance of such tracks, hip-hop fans will recognise many of the lines as having been sampled over the years, including The Original Last Poets' ‘Die Nigga!!!’ having been used as the introduction to N.W.A’s ferocious ‘Real Niggaz Don’t Die’ and elements of Amiri Baraka’s ‘Who Will Survive America?’, which ended up comprising the coda to Kanye West’s My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. The influence was long and the influence was essential. It all started from here. And as a final pointer towards the gulf between the fierce militancy of the Black Power movement and the “turn on, tune in, drop out” hippie ideology, there is a remarkable recording of Eldridge Cleaver discussing placing acid guru Timothy Leary under house arrest in Algiers; identifying how Leary’s astral, lysergic-derived aesthetics were considered the antithesis of the plain-spoken, action-not-words approach of the Black Power movement. Two cultures in the same time and the same space: mutually incompatible and exclusive. Even beneath the stern glare of the establishment who considered both movements an equal threat to American youth, the rift between the two was miles apart. It is a quite fascinating piece of archive audio.

Equally captivating are the inclusion of three tracks from high-profile white artists, all of whom took special interest in the civil rights struggle and used their profile to support the cause. Bob Dylan had always been a fervent champion of civil rights but the inclusion of ‘George Jackson’ (a sparse acoustic piece lamenting the recently slain Black Panther leader who was shot by prison guards in 1971 during a bloody attempted escape) helps identify the point where Dylan returned to his protest roots. Similarly bold is John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s spacey ‘Angela’, a track written in support of the then-jailed political activist Angela Davies (subtly and cleverly referencing Lead Belly’s ‘Sylvie’). But most powerful is Roy Harper’s razor-tipped, stinging ‘I Hate the White Man’: a track that reverberates with cool fury and distain for the actions of his own creed and culture. Sat alongside such bold and forthright statements of Black pride and identity, they serve to perfectly complement the collection and serve notice that the ideology and sense of outrage that characterised Black Power was not simply restricted to the black community. It draws a direct line between the political and social roots of folk music and the similar aims of the Black funk, soul and jazz: two disparate musical movements that searched for the same aim, generations apart. Essentially, this was humans wanting their humanity. It may have been termed Black Power, but they had support from all races and all sides.

It seems furtive, pointless and belittling to give Listen, Whitey a score out of ten. For this record is a historical document as much as it is an album, and it is imperative that it is contextualised as such. In a modern world where hip hop took root in public culture and it is second nature to see a black artist extolling the virtues of their creed and culture, this album intelligently and imperatively reels you within sight of an age where mouths were crying to be heard; an age where equality was not guaranteed; an age where music was both a tool and a weapon in alternative clutches. For a soundbite, the music is magnificent: humorous, scabrous, fierce and mocking in equal measure: a glorious blend of jazz, soul, funk and folk. But the true power of this collection lies not in what it sounds like, but what it helped to crystallise and establish. This was the voice of the angry. This was a voice that shouted when others could only mumble and stammer. This is a chronicle of a crucial chapter in modern and musical history; expressed profoundly and proudly. This is the bubbling, volatile soundtrack to an era that genuinely changed the world.