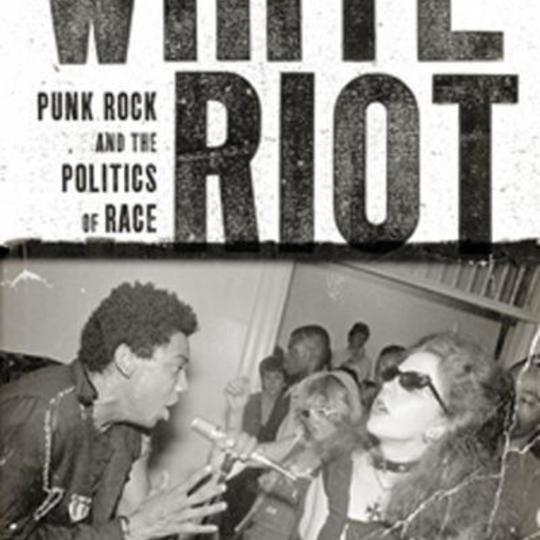

The central problem of punk is this: music that’s simple (to play, to record, to distribute, to imitate) lends itself to the expression of radical politics – challenging racism, sexism, ageism, capitalism, and so on – just as much as it lends itself to less deserving causes (say: embodying all of the above). Like 'the black CNN’ (as Chuck D later called hip-hop) punk reported from the ground before anyone else… but sometimes you couldn’t tell the Rock Against Racism crowd from the skinheads. It’s a problem worth disentangling, and anyone acquainted with punk history knows that Britain’s own punk explosion coincided with the arrival of cultural studies, or its blossoming into something lucid, readable, and (as much as it ever could be) productive; as in, likely to feed into the more sophisticated manifestoes, and recognize actual political engagement.

A reader rather than a scene-history, White Riot instantly raises itself above the various accounts of punk already available, by offering a panopticon of both UK and US punk in the Seventies and early Eighties, tracing its evolution into hardcore and straight-edge, while scattering snippets of numerous essays written on the subject, intelligently selected and edited. If the first half reads like a refocusing of John Savage and Greil Marcus (to bring the black faces in the moshpit into greater resolution), then it’s the second half that goes far beyond their remit by speaking to punks in contemporary Asia, Latin America, the Muslim World and the Third World. For this reader, it’s a lot like reading all those anthropological studies of resistance movements AND possession cults, except: at the same time, and a lot more fun. Punk is as much a political movement as it’s disorganised religion; it’s unafraid of modernity, and while it often gets beaten down (or up) for engaging too violently, it tries to engage with something, which is always a better start than pontificating about what your position should be. (Readers of the New Left Review – also published by Verso – this is for you.)

One objection – and it’s a large one – is that this neglects to contextualize punk-rock as a musical genre AND social movement, other than in relation to a limited range of black genres. Over and over again, we’re told that that reggae was an ‘absent presence’ for punks, or that ideas of 'blackness' were appropriated by whites as a token of their underdog status. In doing so, it becomes difficult for the reader to see how much punk may have achieved, by comparison with other movements. As examples of writing on race issues that could be called 'proto-punk', Duncombe and co-editor Maxwell Tremblay select several excerpts already found in Ann Charters’ (essential) Beat Reader. All are relevant, but Mailer’s The White Negro, and others, basically serve to illustrate white fantasies and projections without linking them to real social changes after Civil Rights (in the US) and the post-WWII surge in immigration (to the UK). Since punk reacted so violently against hippie culture, it would have been useful to survey (however briefly) the shortcomings of the previous mass youth movement to frighten the Establishment.

In Peter Doggett’s impeccable study of the late Sixties counter-culture, There’s a Riot Going On, we see the hypocrisy and rampant misogyny of white and black crusaders alike. Avoiding this, or at least acknowledging the problem, was a major achievement for punk. That said, Doggett showed that the music industry was the first place black Americans achieved autonomy, and demonstrated managerial acumen, without surrendering their cultural identity (as black icons achieving high positions in law or the military had historically done). Where is punk’s comparable achievement? Is it still to come? In a sense, this is the most forward looking book about music I've ever seen, and it would be great to see it catalysing musical discovery as Azerrad's Our Band Could Be Your Life did for the generation after 'the Year Punk Broke' in the US. 'Our' moment (in the UK) may be past, but for the rest of the world, 1977 is just around the corner...

...which might make punk revivals one of the few forms of 'retromania' (as Simon Reynolds puts it) worth endorsing. After all, the single biggest achievement of punk is that it was the first musical movement to try to place men and women on an even footing, which few movements before and since have done; look at the players in the UK between ’76 and ’81, or NYC’s No Wave (corresponding to UK post-punk). If, as this book argues, punk’s attitude, poses, and costumes (highlighting socio-economic bondage) are things that can be taken off by white people, but not by black, then we have to doubt the sincerity of the former, but the whole point of a DIY and/or youth movement is that it doesn’t 'Get Rich or Die Tryin’ but offers a vision, and a design for living, while it can. Any movement that makes young, white and black, men and women more vocal – as well as visibly together – is valuable. Paul Gilroy and Dick Hebdige are here (as well as quotes from Debord, Stuart Hall, and others) to tell us that music offers an imaginary solution to real problems. What they hadn’t yet seen is that when a youth movement grows up, joins the real world, has kids, it doesn’t evaporate, but incorporates as many of those values as it can.

Like I said, though: punk’s a DIY movement. Make your own argument what punk is, was, and should be. The materials are all here.

-

7Alexander Tudor's Score