At one point on Coldplay's fourth album, Chris Martin, millionaire rockstar and male-bride of Oscar-winning Hollywood stalwart Gwyneth ‘homeopathy’ Paltrow, sings: "I'm just so tired of this loneliness".

In 2007, Gwyneth Paltrow starred in a film called The Good Night (directed by her brother), in which she played the girlfriend of an (ex) pop star (played by Martin Freeman of The Office) who dumps said boyfriend due to lack of sex and ambition on his part.

Poor Chris.

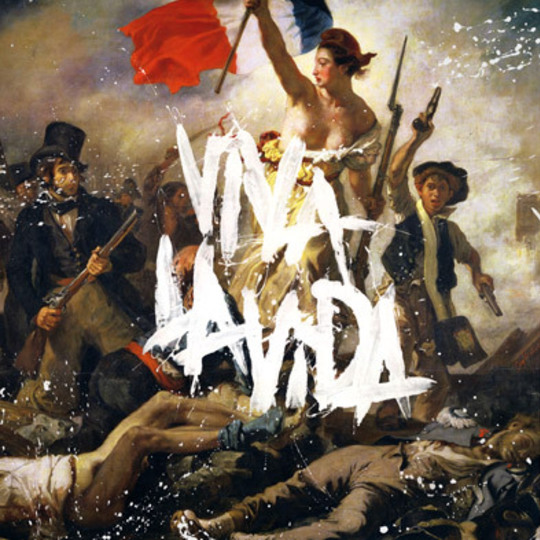

The clunkily-titled Viva La Vida (Or Death & All His Friends), despite grandiose talk of Brian Eno (who handles the bulk of production duties), new directions and experimentalism, reveals precious little about Coldplay that we didn't already know; there are pianos, echoed guitars, plangent chords, drums, bass, and catchy but unremarkable melodies delivered by an unimaginative lyricist who's made millions of pounds out of doe-eyed universal platitudes in the last decade. A Delacroix painting on the cover - you can see pubes! And nipples! And cadavers! - and a title cribbed from Frida Kahlo scream "culture" at you, but Coldplay remain resolutely no-brow, a rock band version of Jack Vettriano; art for people who don't like art; crowd-pleasers for people who don't like crowds; music for people who don't like music.

But nevertheless Coldplay are trying here to broaden their palette, to provide some substance for their success. Chris Martin's recent strops at journalists for not giving his band enough credit for their creativity smack of a man suffering a crisis of confidence in the face of a media determined to brand him a polite entertainer rather than a visionary musician. Viva La Vida is a serious effort to redress this.

So what about the songs? There are definitely efforts to branch out. Obvious verse-chorus-verse configurations, as used ad nauseum by Coldplay previously, are lightly eschewed in favour of slightly more oblique song structures, and so the jaunty pianos and arm-waving stadium rock rhythms of ‘Lovers In Japan’ gives way after a few minutes to the delicate ‘Reign In Love’. Stitching them together into one track with a two-part title seems like indulgent prog frippery, though; there's absolutely no reason for it.

There is apparently reason for album opener ‘Life In Technicolor’ being (largely) instrumental, though; upon being told that ‘Life In Technicolor’ was "the obvious single", Martin and company apparently stripped it of its lyric because they didn't want a safety song on the album. Given the wordplay on display elsewhere, this seems like a wise move. They did, however, leave in just enough punch-the-sky percussion and "oh-oh-oh" vocals to turn it into a suitably stadium-shaking set opener for future tours.

The prog-ness of ‘Lovers In Japan’ and ‘Reign In Love’ is demonstrated elsewhere, too – seven-minute songs called ‘Yes’ with Spanish/Arabic (delete as appropriate)-style strings and ‘Pyramid Song’/‘Karma Police’ (delete as appropriate)-aping choruses (plus the aforementioned lyric about loneliness) don't help your punk credentials, not that punk, in 2008, is any less bereft of cultural worth than prog. About four minutes in, ‘Yes’ goes a little My Bloody Valentine-lite for a mid-album secret track apparently called ‘Chinese Sleep Chant’. It sounds a little like something off Final Straw by Snow Patrol, as heard through a wall.

More orthodox is the 4/4 synth-string anthem title track, which you'll undoubtedly know from the ‘exclusive to iTunes’ advert; the one with the line "I sweep the streets I used to roam". It's very nice, a swooningly romantic tune embellished with all sorts of Eno trickery in the margins and lavished with historical references presumably drawn from Martin's University College London degree in Ancient World Studies. This is followed by the lead single and arguable album highlight, the agreeably nodding guitar machismo of ‘Violet Hill’, which, of course, collapses into a delicate piano coda once the band tires of rocking.

There are clunkers as well, though. ‘42’ starts as a cod-profound piano-ballad with the god-awful lyric "those who are dead / are not dead / they're just living in my head" and a none-more-‘Imagine’ piano fill before, after 90 seconds, drums and guitar tones that, in the context of a Coldplay record, sound a little edgy, drop in and cause a giant middle-eight-cum-chorus to swell up in support of the remarkably dumb line "you thought you might be a ghost / you didn't get to heaven but you made it close". The title, presumably, alludes to the meaning of life as revealed in Douglas Adams' Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy. Thanks for that.

The actually really rather nice ‘Strawberry Swing’, with its padding drums, gossamer lead guitar and understated melody, is unfortunately overshadowed by ‘Death & All His Friends’, which starts small and grows large, becoming the kind of easily repeating, lighters-aloft universal rock anthem-not-anthem that Coldplay have specialised in for years. This in turn, and predictably by this point, is followed by three minutes of ambient dappling and breathy platitudes that might be called ‘The Escapist’ but isn't included in the track listing, and which sounds a little bit like the intro to ‘Where The Streets Have No Name’. It's also, incidentally, the exact same sound that opens the album on ‘Life In Technicolor’. Do you see what they did there?

Coldplay have been chastised enough by critics and naysayers that they want to challenge people a little with this record, and if that means leaving vocals off a song that would have otherwise been a single, or sticking two songs together and pretending they're one song, or trying some watered-down 'world music' percussion, then why not?

The problem is that Coldplay's stabs at radicalism just sound so very safe and familiar. Part of their predicament is the production, which, as with almost any other mainstream rock band of the last 15 or so years, processes, auto-tunes, click-tracks, compresses and otherwise bleeds almost all personality out of the entire band's sound. It could be literally anyone playing guitar, drums, bass or piano on this record, hence why I've not used any names other than Martin's – the backing band are incidental. Even Martin's voice, the group's most distinctive asset, is generally processed to death here – but that's how we're used to hearing him anyway. Gone are the days when you could identify a drummer by both his style of play and the sound of his kit, never mind being able to identify what model of guitar someone is playing from its tone.

Admittedly there's more in the way of textural variation here than on 2005's X&Y, which is presumably down to Eno's involvement, but it's still very, very familiar fare. Largely this is because while Eno's work sounded radical in the ‘70s and early ‘80s when barely anyone sounded anything like him, these days anyone with ProTools can download an Oblique Strategies plug-in and hey presto! Ambient wibbling to fade. As a result Viva La Vida is about as sonically radical as Paul Simon's pleasant but decidedly unradical Eno-produced Surprise album from 2006.

Because unless Coldplay do produce something genuinely radical and creative they're doomed to continue the combination of commercial success and critical indifference which seems to rile their singer even as it lines all of their pockets. So cripplingly keen are they to be shown the same respect as former labelmates Radiohead, for instance, that they dim-wittedly try and ape their heroes on numerous occasions but cock it up slightly each time; where Yorke and companions shook the music industry with the release strategy for In Rainbows, Coldplay's flaccid response is to boldly launch Viva La Vida on a Thursday, like Oasis did with Be Here Now in 1997.

They try hard, Coldplay, but it just isn't enough; their fourth album might just be their best yet, but it's still a long way from being the epochal classic that Chris Martin is desperate to create.

-

6Nick Southall's Score