Twenty years ago today, I stood nervously in the cool late-summer air outside Heaton Manor School awaiting my GCSE results. Little typed numbers on a single piece of A4 paper that would maybe not define, but certainly sharply focus and possibly limit my future paths and options. Standing there, palms reddening with anxiety, I knew how important this moment and these results were to me, and what they would mean for my family and my life to come. Nothing mattered more.

Nevertheless, as I looked around the results hall – at faces of friends, foes and schoolyard fancies – there was a noticeable swathe of people missing. This seemed both disconcerting and baffling to me. What on earth could have been so important that people were missing their GCSE results? Had there been an accident? Zombie Plague? A small but perfectly aligned black hole located entirely over the civic boundaries of Newcastle upon Tyne?

No. The answer was that they were two miles away in the City Centre. Queuing outside either Virgin Megastore, HMV or Our Price. Waiting for an album.

The album in question was the thunderously-hyped third album by Oasis, Be Here Now, out that morning in direct competition to national GCSE results. And befitting of its title, more important and compelling to so many than simple exam results, regardless of their apparent importance in the tapestry of life.

Two decades on, through the mists of time, nostalgia and a changing record industry which seems to fold upon itself at every conceivable opportunity, it is difficult to fully quantify the cultural importance, and then subsequent impact and jeered legacy of Be Here Now. Its contemporary framing is that of a calamitous mistake, a microcosmic definition of Britpop’s absurdities and bloated excess and a serious of over-long and embarrassing sub-Beatles dirges that would have been buried deep underground were it not for the copious quantities of Columbia’s finest energy powder consumed during its six-month gestation. Generally, Be Here Now is an album uniquely scorned and derided – hung on the wall as a reminder of what can happen when the big dream finally goes sour and when cocaine clogs up the faders and dials of the mixing desk and the rational mind.

Yes, there is an element of truth in all those things. Is it overlong? Absolutely. Is it the point where Britpop finally caved in, collapsed and exposed the sordid and turgid underbelly that one of the most thrilling musical scenes in modern history had regressed to? Possibly, though to blame it entirely is to ignore so many shifting cultural sands occurring in tandem with its release. Is it the sound of a fine band falling apart under the sheer weight of impossible expectations? Absolutely and completely.

But truthfully, I’ve never entirely seen those things as absolute negatives. And through all its flaws, I have spent the past two decades staunchly defending Be Here Now as an album which captures its cultural moment like few others, and is actually a far more interesting and multifaceted album than many give it credit for, and an album which does at least deserve a second listen with hindsight.

Let’s get the obvious stuff out the way first. Be Here Now is not a great record. Far from it. It is thunderously bloated and desperately in need of a producer unafraid to stand up to Oasis’s excess and that of their retinue. Five of its songs top seven minutes. The longest (‘All Around The World’) is simply dreadful – a cack-handed and overwrought monstrosity that approximates a low-budget Tenacious D attempting The Beatles rather than hard rock. Oh, and if that’s not enough, they add a reprise to close out proceedings. The answer to any issue of texture and dynamics is simply to yank the faders up to 11, layer on seven more layers of guitar, and double-track. Musically, it is almost totally without grace or compromise, the musical equivalent of a ram raid – devoid of the guile to carry out a cohesive and coherent master plan to pull off the heist, Oasis simply choose to drive the car into the shop front and make off with what they can get.

And yet, once the bluster is swept away, the truth of what it is hiding is frequently fascinating. For a band built on verbal statements of outright intent and arrogance, the lyrics on Be Here Now – while far from poetry – betray a sense of deep insecurity, fear and doubt under the layers of noise. “Do you dig my friends? / Do you dig my shoes? / I am like a child with nothing to lose but my mind” asks Noel on ‘Magic Pie’ as he panics about his importance in the social milieu ahead of the millennium. The protagonist of ‘Stand By Me’ frets and fusses about being left behind and being “Tired of talking on my phone” and unable to cook a simple meal without regurgitation. There is the striking admission – joke or not – under the bluster of ‘My Big Mouth’ with Liam stating, “Everybody knows / They know we’re saying nothing”. Even the jaunty ‘The Girl In The Dirty Shirt’ considers the prospect of when “The hopes and dreams all shatter”.

Some of it may just be the convenience of Noel’s rhyming dictionary, but you cannot shake the feeling that the white noise, the treble-tracked guitars, and the fatuous excess covers an emotional, scared and paranoid core – a songwriter who has succeeded beyond his wildest dreams and then facing up to having to deliver a masterpiece for the age; the bar of expectation set way beyond that even faced by his heroes. If nothing else, this stark juxtaposition is a window into the mind of the songwriter – burdened under expectation, unsure of where to turn, plagued by doubts and attempting to cover them up with pills and powders. In that context, it is hardly surprising that Noel refers to this period as when things got utterly out of hand with his drug use. Imagine being expected – nay, demanded – to deliver the “Album of a Generation”?

Secondly, if you take a second look and ignore the record’s genuinely awful tracks (‘Magic Pie’ and ‘All Around The World’ remain flatly unforgivable in my eyes) there are some fine and unfairly-derided songs on Be Here Now. ‘D’You Know What I Mean?’ remains one of the boldest and most thrilling opening tracks of the decade. It is one of the few songs on the record that fully justifies its excess: throbbing with swagger, churning with arrogance and snarling like a hurricane; swampy drums, jarring strings and a sense of outright danger diving in like military helicopters onto the battlefield. ‘Stand By Me’ – thought shamelessly borrowing from ‘All The Young Dudes’ and at least one John Lennon track – is overwrought and overproduced but stripped back, is melodically radiant and instant. The title track is a gleeful Gonzo glam-stomp and although needing a couple of choruses chopped off, ‘It’s Getting’ Better (Man!!)’ sounds equally like the band having an absolute joy in the studio – their tails up, their enthusiasm back and their skill at knocking something together from nothing on full display.

And then there is the album’s absolute jewel – the bruised but beating heart, the 4am moment of clarity, the peace at the eye of the hurricane. ‘Don’t Go Away’ is quite simply one of Noel Gallagher’s finest moments. It says so much that this is the one song on the record not galvanised or burdened with effects and studio gimmicks – it is simply left to speak in a pure, clear voice; Bacharach horns subtly weaving underneath its sensitive and wistful heart. It is the sound of the melancholy and doubt that underpins Be Here Now, left exposed through the glass and smoke for five glorious minutes before the chaos returns and covers it up. No album with a song this beautiful on it can be truly bad.

Much is made of Be Here Now as being “the album that killed Britpop”. Some of this statement definitely rings true, though it also needs to be considered that the entire pop landscape had changed beyond measure, even in the four months between the record’s wrap and release. Albums such as Radiohead’s OK Computer, The Verve’s Urban Hymns, Blur’s about-take on their eponymous album and other cultural invaders from the periphery such as The Prodigy’s The Fat Of The Land had pushed the cultural envelope more leftfield, more questioning and less-attuned to Oasis’s straightforward brand of guitar rock (as well as a certain Paris car crash ten days later that critically punctured the feel-good media atmosphere of the period). I still firmly believe to this day that if Oasis had released Be Here Now towards the end of 1996, for good or for bad it would be much more highly-regarded in this day and age. But history is written by the winners, and Oasis found themselves also-rans for the first time in their career. They survived, they recovered to an extent, they remained massive. But they were never again the cultural behemoth of Summer 1996 to Summer 1997, although no-one else has even come close since. At least in the UK, they were stratospheric to a degree that’s difficult to even contemplate for anyone born after 1988.

And to come back to where I started, in that school playground all those years ago, if nothing else – Be Here Now deserves acknowledgment in terms of how much it still stands as a cultural totem pole, forever protruding from the musical history of 1997. Never before in my lifetime has an album been so enormously anticipated in British pop music, and I’m doubtful if it ever will be again. This was pre-internet, pre-streaming and with only one single released. Pure hype, pure expectation, pure excitement. People who had built their entire youth on this rag-tag collection of colorful individuals from Manchester saw this as their unique hour of cultural relevance. The fact that the end-result ultimately turned out to be one of disappointment should in no way not airbrush the sheer frisson of those weeks running up to the day of release. It is easy to sneer and scorn in hindsight, but especially in these uncertain and doubt-riven times, this album and this release was a unifying force for so many young people, a sense of a shared belonging for something they all communally adored. Can you imagine a huge number of kids in 2017 missing their GCSE/A-Level results day for an album release? It’s scarcely conceivable. Yet back in 1997, this was such a vital and definitive moment for my fellow peers that it wasn’t even an option. They simply had to hear this album.

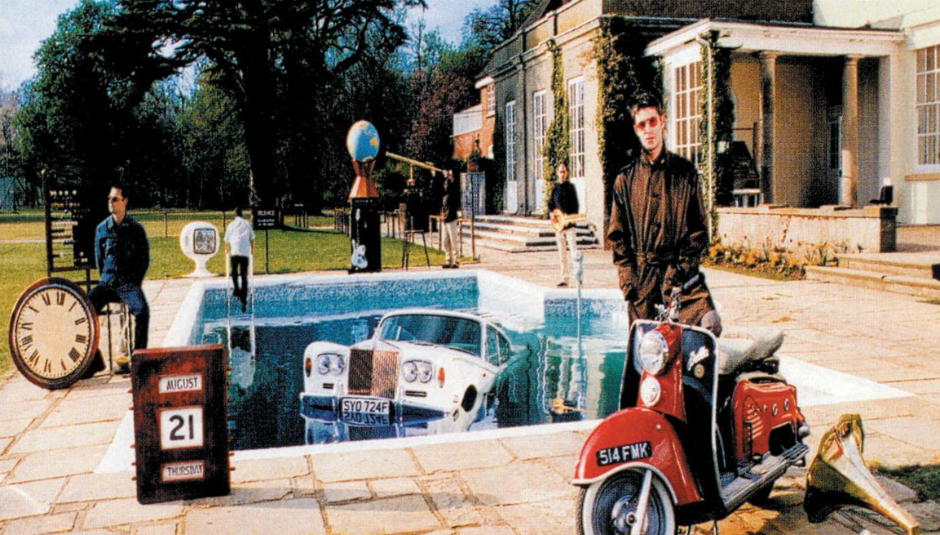

In the bottom left corner of Be Here Now’s (fittingly) cluttered and chaotic album cover, the date of “August 21st – Thursday” is prominently displayed. When I look at this today, I think of a sixteen-year-old kid, high on life and the prospects of the future to come, waiting for confirmation and validation of a summer’s hard work. But I also think of a time when the release of an album meant so much to people that for many, it transcended school, exams and the dull dreary stretch of expected adult life ahead. And isn’t that what rock & roll was always about? Be Here Now is many fathoms away from being a masterpiece but the story under the surface is one of fascinating juxtaposition and its enormous cultural importance (though ultimately proving underwhelming) is unfairly ignored by contemporary commentators.

And let’s stop being afraid to say it in public: there are some bloody great songs on that record. With a stronger hand on the tiller, less excess, and less expectation, things may very well have turned out differently. But there’s often glory in failure, especially the greatest failures. And in the case of Be Here Now, contained within its 71 minutes is a fascinating self–portrait of a band, a time and a movement that may never be replicated or repeated. For that alone, it deserves its unique, strange and unwieldy place in rock and roll history.