Standing outside the muddied canvas of the artist tent at this year’s Standon Calling festival, I try to recall the last time that I was this nervous. It’s been some time. Looking down at the smudged scrawl of my notes I’m pretty sure my hands are shaking, my handwriting suddenly assuming an arcane quality, just baffling lines and shapes divorced from any meaning.

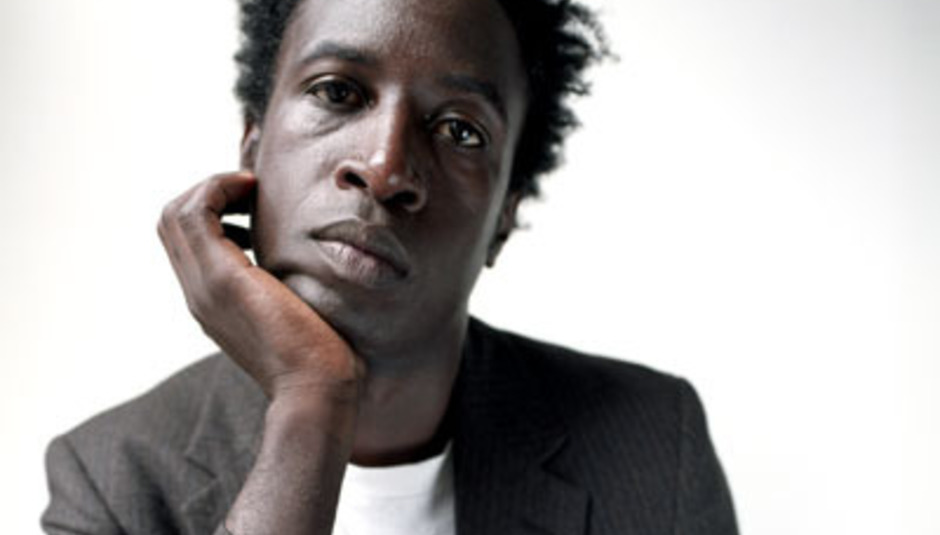

A few moments later and the PR is lifting the flap and gesturing through into a sparse rectangle with just some plastic stools and a battered sofa breaking up the trodden grass. Saul Williams is rising from the latter, one hand outstretched in greeting whilst the other clasps a bottle of beer: he seems taller than remembered, a towering figure, staggeringly intimidating in a way that his smile does little to counteract.

It’s been three years since the last time I met Williams, soaked through with sweat and rain on Brighton’s seafront shortly after his 2008 Great Escape performance at the tiny Volks. On that occasion I barely lasted a minute before my thoughts scattered in fright and I bid an embarrassed farewell: today we have somewhat longer. Well, only five minutes officially, but it’s nearly three times that before Williams pauses for breath, the beer merely warming in his hand as he flits between topics, cadence accelerating as he fires off points like artillery on music, film, politics and Lady Gaga. And, of course, his own new album Volcanic Sunlight, released in May in France and the US but yet to receive a date here.

DiS: Listening to Volcanic Sunrise, it definitely takes a different sound to previous releases. How would you describe it?

Saul: Ah, how would I describe it? I wouldn’t! But if I were to give it a shot I would say that it’s me exploring the possibilities of writing without anger.

So is that a conscious decision then, to remove anger from your work? Previous records have been pretty angry…

Saul: That was the decision for this album, you know. Me and anger still get along pretty well, and I’m sure we’ll collaborate more in the future... But I wanted to do something different - I felt like after Niggy Tardust I needed to explore something different. And also that’s an intellectual idea - just personally I wanted to make music that reflected what I actually listen to a lot.

So what are you listening to?

Saul: At this moment... I’m listening to old stuff right now, like Leonard Cohen and Patti Smith. Everything I’ve been listening to is old with the exception of a few new albums, PJ Harvey and stuff like that. All the other stuff I listen to, like Watch The Throne or something - I listen to that just so I can say ‘I listened to it...’ Oh yeah yeah, I checked it out! So there’s a bunch of stuff that I checked out that’s new, but there’s nothing that’s gone on rotation, with the exception of a few things like Metronomy - that’s been played more than once. I’ve been in more like an old music zone - Kasai Allstars and the Congotronics stuff, and I’ve really been into a lot of polyrhythm and either new African music or dealing with archival tribal recordings. Some of my favourite stuff has been like pygmy albums… I don’t know if there are any pygmy rock stars I can name...

Is that because you’re finding newer artists less interesting…?

Saul: Oh no no, not at all, not at all. No, it’s just me personally - I go through cycles of really wanting to be up on everything that’s out there and not giving a fuck. My purpose for instance with the African tribal stuff - I just finished shooting a film in Senegal for two months, and the director gave me a bunch of music to prepare. It was all this different indigenous music from the continent of Africa, and it’s only been a month since I’ve been back and I’m still kind of in that zone, and so at that point I cut off a lot of stuff because I was acting and needing to be in character so I haven’t really broken out of that mode yet.

What’s the film?

Saul: It’s called Aujourd’hui, which means ‘today’ in French, and it’s the last twenty-four hours in the life of a man who lives in a fictitious African village where the dead come and choose one person, and he wakes up and attends his own funeral, a funeral by the living to say goodbye. It’s all the stuff he wants to do in his last twenty-four hours, and it raises some interesting questions circulating around the idea of living every day like it’s your last.

Does that tie in with your decision to make your new music more positive?

Saul: What’s funny is that my other albums might have been angry but I think they might also be classified as positive. I was never comfortable as a singer, with thinking of myself as a singer - I grew up singing in church and stuff like that but I wasn’t a soloist - and I had to really push myself and challenge myself to feel comfortable singing in public. This album is part of a continuation of that challenge that I gave myself to go though, giving myself license to explore. And once again it was also that idea of making something that is reflective of my personality in all of its circumference as opposed to this is how I channel my anger, you know.

Certainly on initial listens Volcanic Sunlight seems less political than earlier albums. Given that previous tracks such as 'Act 3 Scene 2' very much had an agenda - they’re trying to make a difference - do you feel that you are less political as an artist now?

Saul: I think that it’s impossible for any individual to make a choice that cannot be interpreted as political. For example you get an athlete like Michael Jordan who says "I’m not political" and that’s a political statement, you know. So, I think that there is a world above and beyond the politics of it all and what I aim to do - I’m speaking about volcanoes and the depths and the core of things. When you get to the core of things you’re beyond the politics of race, beyond the politics of gender, beyond the politics of class, but in order to get beyond these politics it seems as if one must first confront these politics. My early albums were me confronting a lot of these things, ending with Niggy Tardust which was me essentially saying you will never hear me fucking reference race again. That’s why it’s called The Inevitable Rise and Liberation, because the end point of that is When I’m done with this, I’m done. I did it. And I felt that the end of that process was accomplished, that I made the album that I wanted to make that confronted and tackled that topic. Now if I were to continue with that it all that effort would just be redundant! But my family and friends never thought of me as an angry person: it’s something that’s been projected through music and what have you, because like I said I’ve channeled things…

Was that a product of the times, do you think?

Saul: It was very much a product of the times, and also a product of the times in which I was born in and raised, and so once opportunity struck me, like - here’s a microphone, some money and some speakers, what you say is going to reach people, I was like if I die tomorrow I want this to be said, I would love for this message to be transmuted through speakers.

Do you think music should have a message?

Saul: I think that every individual approaches music from a different place and in a different way. Perhaps in the same way that you cannot escape politics you cannot escape whatever it is that’s happening in music, and even in that 'Boom Boom Pow' there’s something - although I have no idea what! But, no, not necessarily: I don’t feel that all artists must make the strongest of political statements, must make those ties and observations known. However, if I feel like an artist is trying to escape that, and it’s a time or a moment where it should be addressed or the opportunity is there and it’s not taken advantage of - well, that is noted in my little book...

There’s a view that fewer artists at present are attempting to confront the larger issues…

Saul: I kind of feel the opposite, I feel like right now there’s two things: I feel like the pop machine is crazier and shinier than it’s ever been, more thoughtless and more image-centred than ever. I’m a fan, for example, of Lady Gaga’s presence and image, and I’ve yet to become a fan of the music: it feels like it’s the music that’s suffered there… In the stuff that’s in that realm I feel an emptiness, a vacancy. But then Gaga is addressing something that - perhaps for the gay community especially - is really important for these times and for this day and what have you. But they deserve better music!

There’s an argument that Lady Gaga is slightly cynical in her targeting of that group anyway…

Saul: There is that possibility. Any artist can tune in to the time and say this is a good time to sing a song about this because it’s on the news and if I do that it’ll be a hit...

But do you feel that musicians and artists should be using their voices in a political way?

Saul: I think it’s difficult. For myself right now when I look at the immensity of all that’s happening in the world from the Arab Spring to the London riots to the tsunami, the chaos in Japan and the fall of the economy… All these continual questions about everything that’s been happening globally: Palestine, Israel, all this shit that we are on the cusp of from every angle, the intensity in the youth and the vacancy in the music which speaks of the fact that if that’s vacant then something else is full. How do you address that...?

...In a three minute pop song…

Saul: How do you address that! It is daunting.

Can film do it better, maybe?

Saul: Perhaps, because film is inclusive of all of these feelings. It’s a challenging time, but what’s great about these times, with these failing economies and such, are those individuals who choose to follow their hearts rather than follow their financial ambitions. I applaud any and all artists that attempt to make music, whether it speaks to me or not. I think it’s a worthwhile endeavour, as is writing poetry or theatre or trying to write screenplays or books or novels or painting or building with your hands and all of these things. Because we’re going to find something individually through that process and to me that’s important. It’s like Radiohead said, "You can try the best you can", the best songs already were - so fuck it! It’s never going to be 1968 again and that sucks, it sucks, but we just have to acknowledge it…