They don't make 'em like they used to, do they? Cars, films, local beat bobbies - certainly not singer-songwriters.

That was my initial thought when I began to look back upon some of the genre's chief exponents over the past ten years. And it troubles me, because I've lapped up a fair few of their efforts - Lifted…, Rejoicing in the Hands and Ys in particular have all been on personal heavy rotation at some time or another. Yet, I can't really say that any of the decade's debutants have offered much I'd classify as important. I mean, how many of today's upstarts could really hold a candle to the Dylans, Cohens or Waits' of this world?

I'll acknowledge that the phrase "how they used to make 'em" casts a large net. It has the luxury of being able to refer to anything from within the last fifty years. But that's not what I'm driving at; it's not about time span. Let's even things up and take another ten-year period, the ‘60s, as a sample. Has anyone today gotten close to writing a 'Don't Think Twice, It's Alright', let alone a 'River Man' or even a 'Song to the Siren'? How about a different decade? How about albums this time? Where are the next Nebraskas, Rain Dogs or Tender Preys?

Don't get me wrong, it's not a case of me playing it safe or treating all older music with a greater reverence by default. I never had an issue recognising, say, Is This It or Funeral as truly great upon their release. Yet, if someone chose to equate Fionn Regan's The End of History with After the Goldrush it'd strike me as sacreligious.

Why is that? Why, in my eyes, can't a singer-songwriter arrive on the scene with his or her full splendour there for all to see? I don't think it's a case of a lack of originality being an issue. There's plenty of ground being broken - Owen Pallett is a case in point. Anyway, that's never really been a requirement of the greats. Dylan only ever made two or three albums that could be considered musically adventurous before retreating to the warm shelter of a roots album. He's rarely ventured out since, but it's done his career no harm. He's even heralded for his role as guardian and a torch-bearer for radio era country, blues and folk. No, it's something else.

Is it due to a perceived lack of lyrical flair? I don't think that's an accusation you could level at Joanna Newsom or Sufjan Stevens; still, I don't consider them great. Besides, while it's true that trite lyrics are something the very worst singer-songwriters have in common, so do some of the most revered. Take the first verse of 'Waitin' Around to Die' by the celebrated songwriter Townes Van Zandt for example. It's an amalgam of every country blues cliché you can cram into one song:

Sometimes I don't know where this dirty road is taking me

Sometimes I can't even see the reason why

I guess I keep on gamblin', lots of booze and lots of ramblin'

It's easier than just a-waitin' 'round to die

Yet, consider this: we forgive him these because, you know, he's Townes van Zandt. Hang on just a second. There might be something in this.

You see, Townes van Zandt was a manic depressive. He undertook shock treatment in his youth to try to resolve this but all that did was erase much of his long-term memory. When not busy marrying and divorcing (three times), he spent the majority of his adult life touring dead-end bars and battling, for the most part unsuccessfully, to curb his heroin and alcohol addictions. At one point his habit was so severe that he tried to sell the rights to his first four albums for just $20. He eventually lost his battle with the bottle in the mid-nineties, dying at the age of forty-seven. So, when he sings that verse, our cynicism tends to be dispelled by the pathos he's well-qualified to lend it. Or at least that's the thinking. But do these myths cloud our judgement or enhance it?

Singer-songwriters tend to sing about themselves. Over time, not only do their songs reveal more about the writer, but our knowledge of them is then reinvested to inform our appreciation of the songs. So closely bound are art and artist, in some cases, that we can't really judge one without a full comprehension of the other. That's why, for example, if you've ever heard someone talking up Daniel Johnston to a skeptic, the chances are they'll revert to his incredible back story to support their case. I've done it. I don't feel guilty. It's no different to raving about the video to Johnny Cash's 'Hurt'. It's deeply ingrained within the human condition to seek meaning in everything. In the case of the singer-songwriter, their personal narrative is fundamental to its creation.

This notion of finding meaning in narrative isn't reserved solely for singer-songwriters. We do it with bands as well. However, here the narrative is constructed from different materials. A band represents something pre-defined amongst its members and ready to place within the wider social context it's drawn this definition from. Their dialogue is with the world, and as such is easier to see its relationship with it. That's why a band's debut is often a statement made with their identity already soldered on like a boiler plate, and as such ready to contextualise immediately. If an album from a band is like a polemic in a magazine then a singer-songwriter's is akin to a page from their diary. Self definition is the ongoing dialogue for the singer-songwriter, and one that takes shape over whole bodies of work, rather than just one or two albums.

Think about it: most of the greats took a little while and some re-evaluation before their earliest work was canonised. Dylan, Waits, Bowie, Springsteen: none of these set the world alight with their first efforts, even if retrospective evaluations have been kind to them. Those rare few who have been feted and immediately trumpeted, are those who arrived with a narrative already established - whether it be someone who's launching a solo career after being established in a band or a fella who went and had a cry in a log cabin for a month to get over his ex-girlfriend.

Let's not also forget that the greats have the benefit of context and narrative to justify some truly awful work, as if it was a necessary part of the narrative arc. I'm thinking in particular about Dylan here - I don't want to keep using him as an example but he's the greatest self-mythologiser of them all. Between '76 and '97 he was truly dreadful, save, perhaps, for Oh, Mercy and the long unreleased 'Blind Willie McTell' (which might just be the best thing he's written). It took this period coupled with a major health scare to give the strong, but hardly mind-blowing, Time Out of Mind and everything since the significance it might not otherwise enjoy to this day.

Tom Waits had started to descend into a parody of himself by the early eighties until the co-songwriting of his wife on Swordfish Trombones gave him something new to growl, bark and beatbox about. Beyond his first four albums, Leonard Cohen's output has been patchy. Would we hold him in the same esteem if 'Hallelujah' had been picked up by Alexandra Burke and the OC before John Cale and Jeff Buckley had a chance to save it from its horrible, horrible baby-boomer production and overwrought arrangement? Can we really make too final a judgement on any of the last decade's worth at this stage?

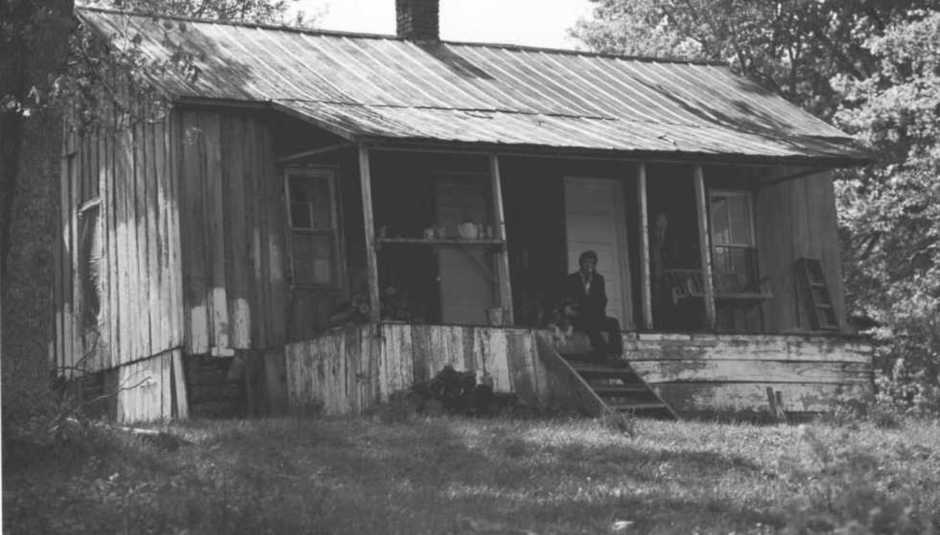

No, no, these things take time. At the moment, it's just too early to tell whether For Emma, Forever Ago is this generation's Astral Weeks; Perfume Genius our Nick Drake; M. Ward about to have his Swordfish Trombones moment; or even Lupen Crook to write a Hunky Dory. Who knows, perhaps there's a genius escaped our attention with their own story well underway elsewhere, just waiting to be seized upon and re-evaluated. Maybe some 40 years down the line this fella, playing what may well be a hollowed out seahorse (about two minutes and fifteen seconds in, for you equine-shaped fish lovers - or haters, depending on your motivation), will record a Rick Rubin-produced, death-bed, roots album. We'll just have to hope and see.