Words by Mikkel Elbech & Michael José Gonzalez // Photography by Martin Dam Kristensen

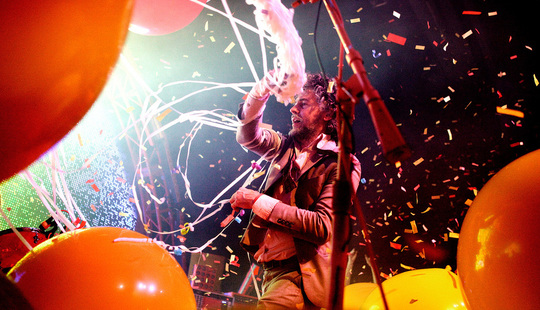

No other band manages to inject so much positive energy into their audience through as spectacular shows as The Flaming Lips. Whether it takes oceans of balloons, rivers of confetti, creative costumes and overwhelming lighting, the musical ambassadors of Oklahoma insist on creating a captivating and unforgettable experience for everyone who shows up to see the band in concert.

As important as the live shows, however, are the band’s studio efforts, and just a few months apart, the sympathetic Oklahomies have released two albums. In October, the world was introduced to the critically acclaimed Embryonic, and most recently they put out their interpretation of the classic Pink Floyd album, Dark Side Of The Moon. Drowned In Sound met up and sat down with the band’s visionary frontman, Wayne Coyne, who enthusiastically opened up the gates to his brightly lit mind.

DiS: How did the idea to redo the Floyd album come about?

WC: A couple of weeks before Embryonic came out I was talking to the people from iTunes. They are very excited when records come out and they get to do things with them. But they always want exclusive material, and I remember that they said, “why don’t we set up this session and you guys can do about seven or eight tracks just for iTunes?”. And I was like, “well, I don’t really have seven or eight tracks”. And as a joke – I swear – I said, “well, why don’t we just record Pink Floyd’s Dark Side Of The Moon?” – just to see what they would say. And about a week later they came back and said, “were you serious about that? ‘Cause we think it would be a really great idea.” I asked Dennis (Coyne’s nephew, and frontman of the band Stardeath And White Dwarfs) if they would do it with us, because then it wouldn’t be such a task, and we could kind of split up the songs. We did it so fast and we didn’t really think about it too much and we changed so many arrangements drastically. We thought, “fuck it, everybody knows this record anyway”.

DiS: How did you get Henry Rollins on board?

WC: I called him to see if he would wanna do the spoken parts. He didn’t even know the record. He claimed that he had only heard it once, which I thought was great. I think he’s a Flaming Lips fan, and I also think he’s really just a fan of interesting things in general, but I figured that he would probably do it. It took him about an hour tops. We sent him some material and he did a couple of different readings that he sent back to us on a hard drive, and it was very intense.

DiS: What does it feel like for you to be creative?

WC: Everything is always a panic. Even making Embryonic. I have no idea if what we do is ever gonna work. But you can look around and think that it probably will. And I don’t really think it has to be the greatest thing ever. I know that sometimes we get very lucky. We’re trying to do something, and it turns into something wonderful. But a lot of times we’re just digging around and it’s not very good. You just have to remember that it’s happened before. And I would probably do it even if nobody else cared. You can’t just do it, ‘cause you think it’s good or ‘cause it’s gonna communicate some great thing. You just have to do it, ‘cause you wanna do it. It’s really like masturbating. You don’t really need any excuse – you just go, “fuck it, I wanna do it”.

DiS: What’s your work ethic?

WC: I’m not lazy. I like doing a lot of things, and to me, it’s all the same thing. A painting, a movie, a song, wearing clothes, talking – even doing this interview – to me, it’s all just me getting to be this weird guy. Free to say what I think! So I just fuckin’ do it, and it does take every bit of your time and your sanity. It’s stressful and all that, but I know that we’re very lucky. We can travel all around the world all the time if we want to. Which we don’t really, but we can travel around and make money and all that. Money’s not really the answer, but everybody in my crew gets paid, and it’s a big crew. I want to have people around me. They’re creative and they have energy, and I want to be around people who like to do things. Nothing stifles you more than being around people, who don’t like to do anything, ‘cause it’s contagious. You guys are curious and you’re energetic, and it makes me that way. But to be around people who aren’t like that has the opposite effect. I wanna be around people who are like, “fuck, Wayne! Let’s do something today”, and I’ll be like, “yeah! Let’s do it!” Usually I’m the first one up, but I wanna be. I want people to know that I’m prepared and I’m ready, if this fails, to try something else.

DiS: Without saying that your intentions were to start a rift with Arcade Fire, it presented itself as one such nonetheless. What are your thoughts on that whole thing?

WC: Well, I think that if you’re a big fan of a group it’s kind of like your football team – anybody that goes against them is automatically the enemy. It’s either “you love us and you’re with us” or “you don’t and we’re against you”, and I can totally see that with Arcade Fire fans or with fans of any group. Every time someone goes against them, they wanna kill you. Especially with me – this weird old guy putting down this new band, but I only said it from my own experience. I’m not saying it about their music or ideas or their organisation, I just say it from my own experience with them.

DiS: So what actually happened?

WC: It was a long time ago – in 2004, I think. We played a show with them, and they were just very rude and impolite. You know, if you think of the worst rock star behaviour that you could think of – they did it. All I’m saying is – you should change, it’s ugly and it lessens the impact of your music, when you’re such divas and so demanding. We were backstage at this festival with Beck, Devendra Banhart and Steve Malkmus, and we were all in our dressing rooms having a good time watching bands and talking about music or our lives or whatever, and then The Arcade Fire came in, and they kicked everybody out. Everybody had to leave. We thought some accident had happened, but they literally just came in and pushed everybody out. They just said, “you can’t be here.” The Arcade Fire demanded that if they didn’t have these dressing rooms they wouldn’t play, and we thought, “well, what do we care, it’s probably their asshole crew or whatever”, but it wasn’t – it was them. We were all excited to see them play, all of us, but they wouldn’t let anybody come near the stage. That’s simply all I’ve said about them, I haven’t said anything about their music, I’m only saying this from my own experience, and they can change. For all I know, they might have. Maybe they’re wonderful people now!

DiS: What’s the first song you remember writing?

WC: In my whole life? I think it was a song called 'Killer On The Radio', and it was very Sex Pistols-inspired, or maybe Ramones. I think the idea was that the music that would be playing on the radio was so bad that it was driving our friends to commit suicide. That would have been a much better title! 'The Bad Local Radio Station Is Making My Friends Commit Suicide'. And you should’ve just told them, “well, don’t listen to the fucking radio”. But that was our dumb response to it. (For those interested: The song was released on Finally, The Punk Rockers Are Taking Acid, a compilation of the first three albums and the band’s self-titled debut ep.)

DiS: What do you think about the song now?

WC: It’s not as embarrassing or as bad or as interesting as you’d want them to be. Sometimes you wanna hear, like, the group that Trent Reznor was in before Nine Inch Nails or something, but it’s not like that. If you don’t like The Flaming Lips now, you won’t like that – and if you do like us, you’ll see something stupid and charming about it. When I hear it now, it doesn’t sound that much different from what the band sounds like now. 25 years on, and we still sound like shit! I don’t think we ever considered ourselves good musicians and singers – especially in the early days – but we thought we could do something interesting with the studio, and I think that’s really the thing that we latched on to.

DiS: While re-watching The Fearless Freaks (the official documentary about the band) in preparation for this interview, a friend said – while watching you go about your things, going around your house with your wife and all your projects, like the “Christmas On Mars” movie – “that guy must have the best life ever”.

WC: I do, yeah! (laughs) I do, but everybody – if they consider their life – could find the same answer. I mean, I have great musicians and artists who are friends, and they really do encourage me and propel me to do this stuff. But I do. I’m sure there are other people whose lives are just as great, but I really am aware that with my house, my wife, our animals, my brothers, I am really lucky.

DiS: You interact with a lot of kids during the movie, and you seem like you would be a great dad. How come you don’t have any kids?

WC: Well, me and my wife decided that we would be free for a while! (laughs) We know a lot of people who have kids, and we do like them. But liking other people’s kids and then having your own – that’s a lot different! But I think we’ll decide within the next couple of years – I mean, I’m 48, but she’s a bit younger than me, so we still have a little bit of time. So we probably will. I mean, we have a lot of animals and things. But that’s a great compliment. Thank you.

DiS: Not to bring you down or anything, but how do you feel about getting older?

WC: Well, I think I’m lucky. I’m 48 now, but when I was 20 I would think, “god, by the time you’re 48, you’re just a wasted old... thing. Your life is over.” But as I’ve gotten older, I’ve seen that you really can accumulate a lot of experiences, and that can turn into knowledge and it can turn into some skills. As far as being an artist goes, being young you’re so fucking insecure. You just want to be cool, you want people to like you, you wanna do your thing, and it’s a struggle ‘cause you always go back and forth. Luckily we have been successful, and it has made me braver. That I’m older and really more healthy than I have ever been, to me that’s the bonus. To be old and not be healthy, that would be a drag, but to be old and have all these experiences and all this stuff, and then to really believe in it and do it and be that thing... I don’t know how long it’ll last – I hope forever, but you know, what are you gonna do?

DiS: The next question was going to be what you’re afraid of, but that might be the answer right there?

WC: No, I’m not afraid of getting old or of death. Mostly the things I’m afraid of are the things I can’t control, like losing my mind – which I probably won’t, because in my family people die before they lose their minds. But I guess that everybody would fear that your family would get killed while you’re out doing this or something – you know, the same dumb fears that everybody has, right? Suffering is worse than death. Suffering changes people and pain changes people. People act like all of these things can be conquered with your mind, but they can’t. Your mind is what you make it, and pain and horrible suffering can change what you value about life. So I’ve been lucky that I haven’t have anything devastatingly horrible happen to me or my family or my friends.

DiS: How come you don’t speak in a Southern accent? Your brothers and the families of Steven and Michael appear to have more of a twang.

WC: Yeah, I know. Well, my parents came from Pittsburgh, which is up north, so they have more of an Eastern accent. I talk so much, and I go around the world so much, but I think that if I was around people from Oklahoma enough some of that would seep into me. And I think the same is true even being here with you guys, there is an element of us trying to accommodate each other. So I become a little bit more European and you become a little bit more American, and we just meet somewhere in the middle, and I think anybody who’s trying to communicate does that. But compared to Europeans I’m sure I sound sort of hillbilly-ish.

DiS: No, not really.

WC: When people think of the southern accent, they often think of the deep south like Georgia and Alabama and Mississippi. And even me, when I’m around people that talk that way, I’m like “wow man, you really got a twang!” It’s even hard to understand sometimes – it’s like being around Scottish people or something. When we first started touring in the eighties, people would say the same thing about us not sounding as if we were from Oklahoma, and I think part of it is that we have grown up with tv and radio, but I’m sure that mostly it’s just my family. If my folks had talked that way, I probably would have too.

DiS: Your music, your performances and your overall vision all seem to make up something that could quite easily be interpreted as being religious – albeit a kind of secular religion. What is being celebrated is not a god or anything, but the here and now, the creativity, the sincerity, having a good time and broadening your mind to new experiences. How do you feel about that interpretation?

WC: Well, I think that’s why religion is so attractive to people. ‘Cause it looks like it’s being in awe of great, powerful things, but a lot of times it’s not. Often it’s just about saying “my religion is better than yours, and if you don’t like it, then fuck you, you’re the enemy”. I’m not religious – at all, really – but there is a religious sense in seeing a mountain, or seeing animals, or having sex, – in having these experiences. In acknowledging them, being moved by them, and thinking that these are significant things. It is in all of the things you conjure with your mind. It is just things that are happening to you. And I think that when I’m luckiest, the Flaming Lips music hints at that part of what I find wonderful about the world. But I don’t always know that we’re doing that. Sometimes I’m singing a song, and I’m thinking, “this is just dumb stuff”, and then someone like Steven (Drozd) or Dave Fridmann (longtime producer) will point out, “that’s that thing that you do!”. And I’ll be, like, “errr…”. I know the song 'Do You Realize??' has that thing, but at first I didn’t really think it was anything at all. “Well, we’ll work on this to see if we can make it into something.” And I was playing it for Steven, and he was really like, “um, that’s one of those Wayne classics!”. And I remember asking him, “should we change the line ‘everyone you know some day will die’?”, and he’s like, “no, that’s the line!”. But as much as when you say those things, I’m aware that Flaming Lips music does that, I don’t necessarily think it’s me.

DiS: No, no, it’s the whole thing. It wasn’t to put you on a pedestal and call you “God” in that sense. Or a prophet, even. It’s more that The Flaming Lips as such is representative of what could be said to be a godless religion.

WC: Right, right. I think that’s the power of our music. It does have the power to make these little, ordinary moments seem like epic things. And I don’t think that’s what religion does in that sense. In the best sense, it would seem like it would tell you that your life is epic – you just have to be aware of it. You know, a lot of people aren’t aware of the beauty that’s all around them already. But I’m lucky – the people who like our music are kind of like us. So I don’t really run into much opposition! (laughs)

DiS: An overall message in your music seems to be about unity and celebrating that thousands of people can gather and have a good time together – and it does create a strong sense of unity when you are in the crowd at a Flaming Lips show. But, on the other hand, I’m sure that you wouldn’t argue against the value of personal freedom. So, how do you balance unity and collective thinking on one side, and then individuality and personal freedom on the other?

WC: Us as a group on stage, we could say, “you know, we’re gonna play some music, but it’s really for us – even though we know there’s people out there”. Or we could say, “let’s include them in it and see what happens”. It’s like you have another element to play with. So that’s a conscious effort that we make. But I also think the audience can do that. I mean, I do this all the time – I go to rock concerts, where the whole audience is going ape shit, and I can kind of stand there and not do it and still have a great time. Or I can surrender to it, and just be one of the happy idiots going along with whatever it is and I can like that, too. So I don’t think we’re suggesting you should drop your personal freedom – but I’m just saying that this is only something we can do, if we’re all together – you can’t really experience this by yourself or by watching tv or being on the Internet. These are sort of cosmic connections that can only be made when everybody is believing in the same experience at the same time. So, I look at it like this – I don’t know what you’re doing tomorrow, but right now we’ve got all this music, we’ve got all you guys, we have all this energy, all this love – let’s do this thing. And I think the audience wants to do it. I don’t think they’d be there, if they didn’t wanna do it.

DiS: Have you ever, while being on stage during a show, spotted a crowd member, who was just not into it and then that really bugged you?

WC: Oh, every night. My feeling is that they’re there, so they care somewhat. But almost every night, there’ll be plenty of happy and enthusiastic faces out there, and at some point I’ll be thinking, “man, this is really the greatest show ever!”, and I’ll look at a guy, and he’s yawning, and, I swear, he’ll look at his watch while I’m singing! And I’m, like, “weeell, there you go”. He’s thinking about, well, he’s got to get up for work tomorrow. But that’s what I want! I want this to be a real experience. I don’t want people to ever think that, “oh, this is better than life”. This is life. You’re here, ‘cause you like music. You’re here ‘cause you like these experiences, but these experiences shouldn’t be better than your life. Your life really should be about this stuff anyway. And it’s really not about us. That’s what I try to tell people. I’m here to do whatever I can to entertain you, to help you have sex tonight, to help you get high – I don’t care whatever it takes.

DiS: Would you classify what you’re doing as art?

WC: I know what we do is art in some way, but not actually when we’re performing. There’s a lot of it that is just entertainment. A lot of bands would never wanna say that, ‘cause they think entertainment is schmaltzy Hollywood bullshit, and that rock n’ roll is some kind of authentic being. But it can’t be. Otherwise it would just drive you crazy. If I had to stand there every day, after getting two hours of sleep, being in some weird venue, having electronic problems or whatever, and I then had to think, “oh, now I have to be an artist right in front of you” – no one can do that. And no one ever really has. So you develop this routine, and if everything goes right, it takes you along with it. And I’m being taken along with this music and this experience as well. I can stand there and think, “I wish I had another Red Bull” and “I wish I was more awake”, but once the audience and the music starts to go, I become awake – and better than I am. So we’re making it happen. Not just for the audience, but for ourselves – for the whole experience.